Creating a Plugin

Improve this pageThis is an abstract overview of how to add positional audio support; for step-by-step instructions, see the Pluginguide.

What is needed for positional audio

For positional audio, we need two things: Your position in the 3D world, and the direction you are looking in. If you have access to the source code for the game, exporting this to Mumble is easy, just use the Link plugin. If this is a 3rd party game, we’ll have to extract the position from the running game.

If you have any questions regarding the process hit us up in #mumble-dev:matrix.org and we will try to help.

We also accept new plugins into our codebase as long as you are willing to support them. Be aware however that we might reject plugins for games with short update cycles as our current distribution method makes keeping those working for longer times quite painful. When in doubt please verify with us before puttin in the work.

Data

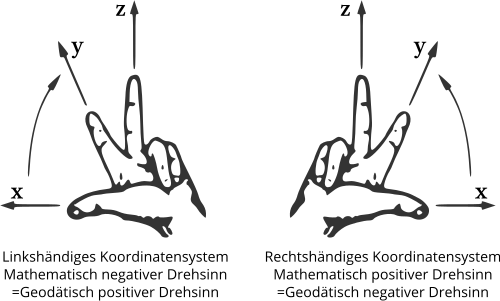

Mumble, like most sound systems, uses a left handed coordinate system (see this for a visual representation).

As a visualization of the left handed coordinate system: If you imagine yourself looking over a large empty field; X increases towards your right, Y increases above your head, and Z increases in front of you. In other words, if we place origin in your chest and you stretch your arms out to your sides, your right hand will be (1,0,0), your left hand will be (-1,0,0) and your head will be (0,0.2,0). If you then stretch your arms out in front of you instead, they’ll become (0,0,1).

We need three vectors. First is the position vector. This should be in meters, so you may need to scale it. The reason: If it is not in meters, distance attenuation will be different to the other games/plugins, meaning users will have a bad experience with positional audio (audio configuration is dependant on a common distance measurement).

The next two vectors are the heading. These should be unit vectors (length one), and should be perpendicular (to one another). The first vector is the front vector, which is simply the direction you are looking in. The second is the top vector, which is an imaginary vector pointing straight out the top of your head. If you do not supply a top vector, Mumble will assume you have a “Y-is-up” coordinate system and that the user can not tilt their head, and then compute the top vector based on that.

Method 1: Memory Searching

Warning: Be aware that the tools/methods used in this tutorial might trigger anti cheat protection. Read the sections below carefully before attempting to use them on a game.

Note that Mumble does NOT support cheating of any kind.

This works well for most games which think of the player as a static object, meaning the data’s location in memory is fixed. This is the fastest method, so it’s recommended you start with this.

Initial setup

First, start the game, read the documentation, websites, whatever you can find, and see if there is a way to have the game display your current position. If there is then you’ll have a much easier time validating your data.

Then start the game. Try to find a piece of geometry that’s aligned along an axis; if there’s a compass or minimap, point due north.

Finding the position offset

Start your preferred cheating utility.

If you don’t have it, choose one from the list under Memory Analysis Tools.

If you have the in-game position

Search for a floating point value around the X value. (IE, if the game reports your position as 357.3, search for a value between 357.2 and 357.4). Move a bit, repeat. When you’ve narrowed it down to just one possible address (or set of addresses), write them down.

Repeat for Y and Z.

If you don’t have the in-game position

Make a memory snapshot. Move forward. Search for a floating point value that increased. Move backward. Search for a floating point value that decreased. Repeat. If you don’t find any values at all, the game might have reversed the axis; so turn 180 degrees and try again.

When you find the X value, turn 90 degrees right and search for the Y value, and then the Z value.

When you have the positions

Based on the addresses you have, we’re looking for just one triplet of (XYZ) addresses. They should be right next to each other in memory, ideally 4 or 8 bytes apart. Note down all positions that match.

Now, and this is important; quit the game, restart your machine and start the game again, but this time do so with a different map, a different character, different graphics settings, different audio; in short, change everything you can but the actual game.

Start your cheat utility again and go through all the addresses you have. If they still match, you can use this method. If they don’t, the game dynamically allocates the position in memory, and you’ll have to use another method.

Finding the heading

Once you have the position, you can find the heading with the same method. Since you now know what is the positive direction of the X axis, position yourself so you are looking straight down it. Your ‘front’ heading should be (1,0,0), so search for a floating point value between 0.7 and 1.05. Turn 180 degrees and search for a value between -0.7 and -1.05. Repeat for Y and Z.

The top vector is done the exact same way, just look down into the ground when finding X; your head now points along the X axis. Note that some games do not have a top vector; a top vector is only “needed” if the game allows you to tilt your head from side to side.

Peeking at the code

This is the second method, to be used if the first doesn’t work. Note that this method requires advanced disassembly knowledge, so if you’re capable of doing this, you probably don’t need a guide. So, this will be brief.

Quality disassembly

You need a quality disassembler or debugger. A good one is IDA Pro, but it’s a tad expensive.

Finding the game’s positional audio

The trick we’re going to use is this; most games already have positional audio support, so we’re looking for their audio code. Their audio code needs the position and heading, so we simply rip that particular piece of data :)

Note that most games will rotate and move the game world; they will set the listener to always be at origo, looking straight down the Z axis, and then they will rotate and translate all the sound-sources before passing parameters to the sound system (OpenAL/DirectSound/FMOD). We found this out the hard way; we had a really cool plugin which injected into OpenAL and DirectSound and took the position of the speaker from there, but in 90% of the games that gave us origo instead.

First you need to figure out which sound technology the game uses, and then proceed from there.

FMOD

If it’s using FMOD, it will say so in the documentation and most likely on the loading screen. FMOD can be statically linked to the application. If it is, you’re going to have a much harder time of things. If it’s a DLL, you can find the import table and backtrack the calls to find the game’s audio routines.

OpenAL

OpenAL will always be loaded dynamically, so just start the game, break it in a debugger and look for the openal, openal32 etc libraries. If it’s there, the game is using OpenAL.

DirectSound

If the game is using directsound, it will load the dsound.dll, and will at some point call DirectSoundCreate8(). Search for the call, find out where the game stores the object pointer and look for other routines which access it.

Using a debugger to speed things up

You can speed things up considerably by using a debugger and some creative breakpointing. Set a breakpoint on all the functions in the Audio API which set the position of either the listener or the source. The game will break, and the stack backtrace will give you the module offsets for the audio code.

What to do when you have the code?

With a bit of luck, the code for setting the source position includes some fancy matrix multiplication; the matrix being multiplied with is based on your current position and heading, so find the code which computes it and you’ll have your ingame position and heading.